I have updated my bibliography on the Extreme/Radical Right in Europe with 53 new titles. To find out what is new, watch the 90-second video, or read the brief summary.

Category: Political Science

The Bibliography on the Extreme Right in Europe: Winter 2019 update

Depending on your point of view, autumn is late this year. Or Christmas comes early. Either way, here is the winter 2019 edition of the Eclectic, Erratic Bibliography on the Extreme Right in Western Europe. And this is what you will want to know ? How much is new in the bibliography? Since March, I have…

Frauke Petry’s Blue Party is over

When former leader Frauke Petry left the AfD after the 2017 federal election, she kept her seats in the Bundestag and in Saxony’s regional parliament. These seats were meant to form the base for a new movement/party she quickly set up with friends and family. [caption id="attachment_29025" width="1200"] Image source: Wikipedia[/caption] The “Blue Party” was…

5 quick hits on the state election in Thuringia

LEFT 30.4% AfD 23.5% CDU 22.1% SPD 8.1% GREENS 5.1% FDP 5.1% Source: FGW projection, 8:10pm Why waste my life writing lengthy books that no-one is going to read? Why go through the pain of peer review? Why, in fact, wait for the actual election results to come in? So here is my list on…

Another AfD leader speaks at a far-right “institute”

The ‘Institut für Staatspolitik’ is a well-known far-right ‘think tank’. Their self-stated meta-political mission is to educate the future nationalist. The long-term objective is to achieve a stealthy transformation of German society. They have been around for a while, and there are books and chapters about them, written by people who study right-wing extremism for…

Video: The AfD’s transformation, 2013-2017

The “Alternative for Germany” began its political life as a softly eurosceptic breakaway from the political mainstream but has changed beyond all recognition. Using a very large dataset covering the full 2013-17 period, Carl Berning and I trace the transformation of the AfD’s electorate, which now fits the somewhat stereotypical radical right template. Read the full article, or watch the highlights in just under 90 seconds.

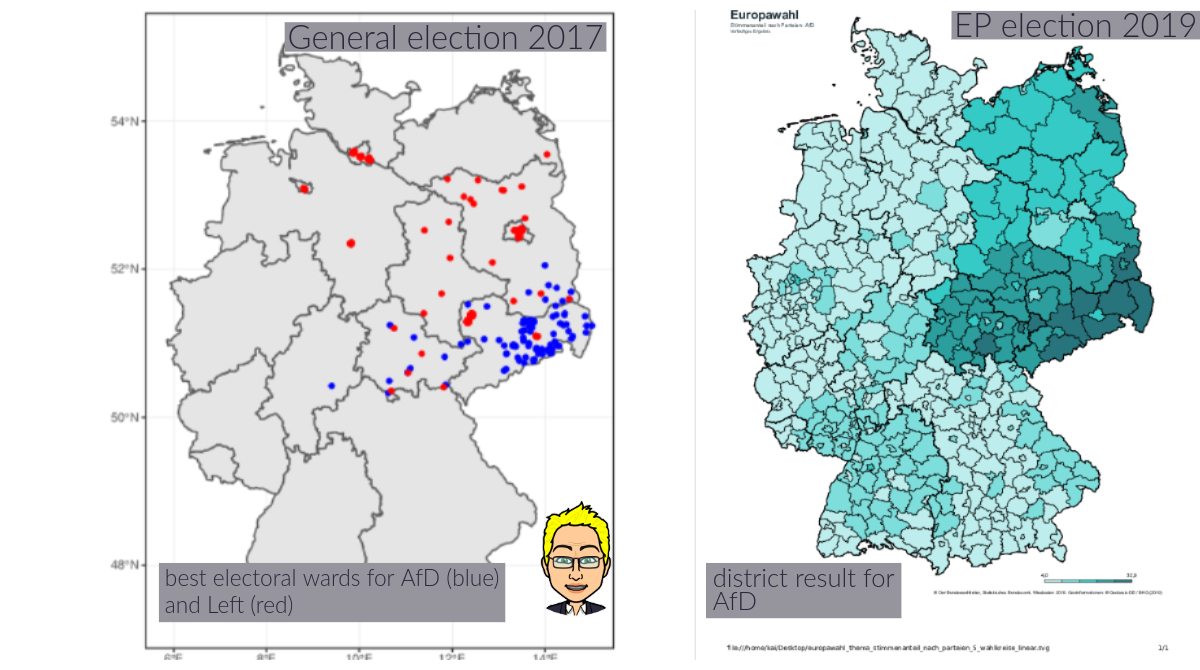

Regional support for the “Alternative for Germany” varies wildly

The AfD was founded near Germany’s financial centre of gravity (Frankfort) by members of the old western elites. But early on, the eastern states of Brandenburg, Saxony, and Thuringia became important for the further development of the party. It was here, during the 2014 state election season, that the AfD began to toy (very reluctantly…

4 quick takes on the result of the 2019 European Elections in Germany

[caption id="attachment_28859" align="alignnone" width="884"] Results of the EP 2019 in Germany (exit polls as of 7pm)[/caption] It will take some time to get nearly-final results for Germany, let alone for the EU, but the picture emerging from the exit polls in Germany is reasonably clear. So, in time honoured tradition, here are my hot takes:…

The EP 2019 brings all the (neo-fascist) boys to the yard

Germany – no EP electoral threshold for the last time There are currently 111 ‘political associations’ registered with Germany’s federal electoral commission. 41 of them (counting the CDU and the CSU separately) are fielding candidates in the upcoming European elections.Why are they doing it? Narcissism aside, this is a national election that is held without…

Alter Pre-Print: Die Bundestagswahl 2013 in Ost-West-Perspektive

Drei Jahrzehnte nach der Wiedervereinigung unterscheiden sich Lebensumstände, Erfahrungen, Einstellungen, Wertorientierungen und politische Verhaltensweisen von Ostdeutschen und Westdeutschen immer noch deutlich. Im Wahlverhalten zeigt sich dies unter anderem darin, dass in den neuen Ländern Nichtwähler- und Wechselwähleranteile höher sind als im Westen. Auch bei der Wahlentscheidung gibt es fast schon klischeehafte Unterschiede: im Westen schneiden…