Identification with an Anti-System Party Undermines Diffuse Political Support: The Case of Alternative for Germany and Trust in the Federal Constitutional Court

Kai Arzheimer1

Abstract: The rise of the far right is increasingly raising the question of whether partisanship can have negative consequences for democracy. While issues such as partisan bias and affective polarization have been extensively researched, little is known about the relationship between identification with anti-system parties and diffuse system support. I address this gap by introducing a novel indicator and utilising the GESIS panel dataset, which tracks the rise of a new party, “Alternative for Germany” (AfD) from 2013, when the party was founded, to 2017, when the AfD, now transformed into a right-wing populist and anti-system party, entered the federal parliament for the first time. Employing a panel fixed effects design, I demonstrate that identification with “Alternative for Germany” reduces trust in the Federal Constitutional Court by a considerable margin. These findings are robust across various alternative specifications, suggesting that the effects of anti-system party identification should not be dismissed.

Introduction and outline

For many citizens, party identification is a political attitude so central that it has been dubbed the “ultimate heuristic” (Dalton 2016): it provides valuable cues to all aspects of political life. The consequences of this are widely seen as beneficial. Partisanship increases turnout and other forms of political participation (McAllister 2020). By structuring political choices, it may also stabilise electoral politics and can help to limit the short-term impact of political crises (Dalton 2016, 8–9). More generally, party identification is assumed to increase support for the political system (Holmberg 2003). Dealignment, i.e. the decline of partisan ties observed in many European countries, is therefore often deemed problematic (Dalton and Wattenberg 2000).

More recently though, research has focused on two negative consequences of partisanship. First, precisely because party identification is such a powerful heuristic, it can strongly bias perceptions of politicians’ competence and issue positions and consequently lead to electoral choices that go against one’s stated preferences (Dalton 2020). Second, and apart from such genuinely political misperceptions, its social-identity component may cause affective polarisation, a state where society is divided along partisan lines into different camps that dislike and distrust one another (Iyengar et al. 2019).

A third negative consequence of partisanship, however, is rarely discussed in the literature: identification with an anti-system party may undermine diffuse support for (democratic) political systems. This gap is somewhat surprising: during the inter-war period, anti-system parties have aimed at and often succeeded in destroying democracy in Europe from within. More recently, populist anti-system parties (often, but not always members of the radical right or radicalised mainstream right)2 have again emerged as a force that is causing democratic erosion, or backsliding, even in fairly established democracies (Foa and Mounk 2017; Waldner and Lust 2018; Diamond 2021).

While anti-system parties consciously place themselves outside the political consensus, many of them have existed long enough for their supporters to develop an identification with them. And yet, the extant literature on the nexus between party identification and system support relies chiefly on data collected more than two decades ago, before the current fourth wave (Mudde 2019) of far right mobilisation fully began. More research into the link between far right party identification and declining diffuse support for the (democratic) political system is therefore needed.

The aim of this contribution is to empirically test whether identification with an anti-system party does indeed causally reduce system support in contemporary stable democracies. To this end, I first review the existing evidence for such an effect. Following that, I show how a conceptual clarification and the use of alternative indicators and designs could improve upon previous research. I then introduce Germany as a country case. Here, the emergence of a new soft-eurosceptic entity that quickly transformed into an anti-system, radical right party coincided with the launch of a panel study that is particularly well suited for the research problem at hand. Finally, after considering data and methods, I present the results and discuss their implications.

- Arzheimer, Kai. “Im Osten nichts Neues? Die elektorale Unterstützung von AfD und Linkspartei in den alten und neuen Bundesländern bei der Bundestagswahl 2021.” Wahlen und Wähler – Analysen zur Bundestagwahl 2021. Eds. Schoen, Harald and Bernhard Weßels. Wiesbaden: Springer, 2024. 139-178. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-42694-1_6

[BibTeX] [Download PDF] [HTML]@InCollection{arzheimer-2023c, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {Im Osten nichts Neues? Die elektorale Unterstützung von AfD und Linkspartei in den alten und neuen Bundesländern bei der Bundestagswahl 2021}, booktitle = {Wahlen und Wähler - Analysen zur Bundestagwahl 2021}, publisher = {Springer}, year = 2024, editor = {Schoen, Harald and Weßels, Bernhard}, address = {Wiesbaden}, url = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/bundestagswahl-2021-ostdeutschland-linkspartei-afd.pdf}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/bundestagswahl-2021-ostdeutschland-linkspartei-afd/}, dateadded = {14-11-2022}, doi = {10.1007/978-3-658-42694-1_6}, pages = {139-178} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “Identification with an anti-system party undermines diffuse political support: The case of Alternative for Germany and trust in the Federal Constitutional Court.” Party Politics online first (2024): 1-13. doi:10.1177/13540688241237493

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [HTML]The rise of the far right is increasingly raising the question of whether partisanship can have negative consequences for democracy. While issues such as partisan bias and affective polarization have been extensively researched, little is known about the relationship between identification with anti-system parties and diffuse system support. I address this gap by introducing a novel indicator and utilising the GESIS panel dataset, which tracks the rise of a new party, “Alternative for Germany” (AfD) from 2013, when the party was founded, to 2017, when the AfD, now transformed into a right-wing populist and anti-system party, entered the federal parliament for the first time. Employing a panel fixed effects design, I demonstrate that identification with “Alternative for Germany” reduces trust in the Federal Constitutional Court by a considerable margin. These findings are robust across various alternative specifications, suggesting that the effects of anti-system party identification should not be dismissed.

@Article{arzheimer-2024, author = {Kai Arzheimer}, title = {Identification with an anti-system party undermines diffuse political support: The case of Alternative for Germany and trust in the Federal Constitutional Court}, journal = {Party Politics}, year = 2024, volume = {online first}, pages = {1-13}, keywords = {EuroReX, AfD}, abstract = {The rise of the far right is increasingly raising the question of whether partisanship can have negative consequences for democracy. While issues such as partisan bias and affective polarization have been extensively researched, little is known about the relationship between identification with anti-system parties and diffuse system support. I address this gap by introducing a novel indicator and utilising the GESIS panel dataset, which tracks the rise of a new party, "Alternative for Germany" (AfD) from 2013, when the party was founded, to 2017, when the AfD, now transformed into a right-wing populist and anti-system party, entered the federal parliament for the first time. Employing a panel fixed effects design, I demonstrate that identification with "Alternative for Germany" reduces trust in the Federal Constitutional Court by a considerable margin. These findings are robust across various alternative specifications, suggesting that the effects of anti-system party identification should not be dismissed.}, doi = {10.1177/13540688241237493}, pdf = {https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epub/10.1177/13540688241237493}, html = {https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/13540688241237493} } - Arzheimer, Kai, Theresa Bernemann, and Timo Sprang. “Oppression of Catholics in Prussia Does Not Explain Spatial Differences in Support for the Radical Right in Germany. A Critique of Haffert (2022).” Electoral Studies 89 (2024): 102789. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2024.102789

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [HTML]A growing literature links contemporary far-right mobilization to the “legacies” of events in the distant past, but often, the effects are small, and their estimates appear to rely on problematic assumptions. We re-analyse Haffert’s (2022) study, a key example of this strand of research. Haffert claims that historical political oppression of Catholics in Prussia moderates support for the radical right AfD party among Catholics in contemporary Germany. While the argument itself has intellectual merit, we identify some severe limitations in the empirical strategy. Retesting the study’s cross-level interaction hypothesis using more suitable multi-level data and a more appropriate statistical model, we find a modest overall difference in AfD support between formerly Prussian and non-Prussian territories. However, this difference is unrelated to individual Catholic religion or to the contextual presence of Catholics. This contradicts the oppression hypothesis. Our study thus provides another counterpoint to the claim that historical events have strong and long-lasting effects on contemporary support for the radical right. We conclude that simpler explanations for variations in radical right support should be exhausted before resorting to history.

@Article{arzheimer-bernemann-sprang-2024, author = {Arzheimer, Kai and Bernemann, Theresa and Sprang, Timo}, title = {Oppression of Catholics in Prussia Does Not Explain Spatial Differences in Support for the Radical Right in Germany. A Critique of Haffert (2022)}, journal = {Electoral Studies}, year = 2024, volume = 89, pages = 102789, abstract = {A growing literature links contemporary far-right mobilization to the "legacies" of events in the distant past, but often, the effects are small, and their estimates appear to rely on problematic assumptions. We re-analyse Haffert's (2022) study, a key example of this strand of research. Haffert claims that historical political oppression of Catholics in Prussia moderates support for the radical right AfD party among Catholics in contemporary Germany. While the argument itself has intellectual merit, we identify some severe limitations in the empirical strategy. Retesting the study's cross-level interaction hypothesis using more suitable multi-level data and a more appropriate statistical model, we find a modest overall difference in AfD support between formerly Prussian and non-Prussian territories. However, this difference is unrelated to individual Catholic religion or to the contextual presence of Catholics. This contradicts the oppression hypothesis. Our study thus provides another counterpoint to the claim that historical events have strong and long-lasting effects on contemporary support for the radical right. We conclude that simpler explanations for variations in radical right support should be exhausted before resorting to history.}, html = {https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0261379424000477}, pdf = {https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0261379424000477/pdfft?md5=8b0c75faf974eb845135c7c1e0f41c14&pid=1-s2.0-S0261379424000477-main.pdf}, doi = {10.1016/j.electstud.2024.102789} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “Die AfD und Russland.” Jahrbuch Extremismus und Demokratie. Eds. Backes, Uwe, Alexander Gallus, Eckhard Jesse, and Tom Thieme. Vol. 36. Nomos, 2024. 207-220.

[BibTeX] [HTML]@InCollection{arzheimer-2024b, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {Die AfD und Russland}, booktitle = {Jahrbuch Extremismus und Demokratie}, pages = {207-220}, publisher = {Nomos}, year = 2024, editor = {Uwe Backes and Alexander Gallus and Eckhard Jesse and Tom Thieme}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/afd-russland-verbindung/}, volume = 36, dateadded = {25-06-2024} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “The Electoral Breakthrough of the AfD and the East-West Divide In German Politics.” Contemporary Germany and the Fourth Wave of Far-Right Politics: From the Streets to Parliament. Ed. Weisskircher, Manès. London: Routledge, 2023. 140-158.

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [HTML]The radical right became a relevant party family in most west European polities in the 1990s and early 2000s, but Germany was a negative outlier up until very recently. Right-wing mobilisation success remained confinded to the local and regional level, as previous far-right parties never managed to escape from the shadow of “Grandpa’s Fascism”. This only changed with the rise, electoral breakthrough, and transformation of “Alternative for Germany” (AfD), which quickly became the dominant far-right actor. Germany’s “new” eastern states were crucial for the AfD’s ascendancy. In the east, the AfD began to experiment with nativist messages as early as 2014. Their electoral breakthroughs in the state elections of this year helped sustain the party through the wilderness year of 2015 and provided personel, ressources, and a template for the AfD’s transformation. Since its inception, support for the AfD in the east has been at least twice as high as in the west. This can be fully explained by substantively higher levels of nativist attitudes in the eastern population. As all alleged causes of this nativism are structural, the eastern states seem set to remain a stronghold for the far right in the medium- to long-term.

@InCollection{arzheimer-2021, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {The Electoral Breakthrough of the AfD and the East-West Divide In German Politics}, booktitle = {Contemporary Germany and the Fourth Wave of Far-Right Politics: From the Streets to Parliament}, publisher = {Routledge}, editor = {Weisskircher, Manès}, year = 2023, pages = {140-158}, address = {London}, abstract = {The radical right became a relevant party family in most west European polities in the 1990s and early 2000s, but Germany was a negative outlier up until very recently. Right-wing mobilisation success remained confinded to the local and regional level, as previous far-right parties never managed to escape from the shadow of “Grandpa’s Fascism”. This only changed with the rise, electoral breakthrough, and transformation of “Alternative for Germany” (AfD), which quickly became the dominant far-right actor. Germany’s “new” eastern states were crucial for the AfD’s ascendancy. In the east, the AfD began to experiment with nativist messages as early as 2014. Their electoral breakthroughs in the state elections of this year helped sustain the party through the wilderness year of 2015 and provided personel, ressources, and a template for the AfD’s transformation. Since its inception, support for the AfD in the east has been at least twice as high as in the west. This can be fully explained by substantively higher levels of nativist attitudes in the eastern population. As all alleged causes of this nativism are structural, the eastern states seem set to remain a stronghold for the far right in the medium- to long-term.}, keywords = {eurorex,afd}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/paper/afd-east-west-cleavage-breakthrough/}, dateadded = {12-04-2021} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “To Russia with love? German populist actors’ positions vis-a-vis the Kremlin.” The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-Wing Populism in Europe. Eds. Ivaldi, Gilles and Emilia Zankina. Brussels: European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), 2023. 156-167. doi:10.55271/rp0020

[BibTeX] [Abstract]Russia’s fresh attack on Ukraine and its many international and national repercussions have helped to revive the fortunes of Germany’s main radical right-wing populist party ‘Alternative for Germany’ (AfD). Worries about traditional industries, energy prices, Germany’s involvement in the war and hundreds of thousands of refugees arriving in Germany seem to have contributed to a modest rise in the polls after a long period of stagnation. However, the situation is more complicated for the AfD than it would appear at first glance. While many party leaders and the rank-and-file have long held sympathies for Putin and more generally for Russia, support for Ukraine is still strong amongst the German public, even if there is some disagreement about the right means and the acceptable costs. At least some AfD voters are appalled by the levels of Russian violence against civilians, and the party’s electorate is divided as to the right course of action. To complicate matters, like on many other issues, there is a gap in opinion between Germany’s formerly communist federal states in the East and the western half of the country. As a result, the AfD leadership needs to tread carefully or risk alienating party members and voters in the more populous western states. Beyond the AfD, the current and future consequences of the war have galvanised the larger far-right movement, particularly in the East. Moreover, they have led to further tensions in the left-wing populist “Linke” (left) party, which is traditionally pacifist and highly sceptical of NATO. The majority of the party tries to square commitment to these principles with solidarity with the victims of Russian aggression. A small but very visible faction, however, shows at least a degree of support for Russia and blames NATO and the US for the war.

@InCollection{arzheimer-2023e, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {To Russia with love? German populist actors' positions vis-a-vis the Kremlin}, booktitle = {The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-Wing Populism in Europe}, publisher = {European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS)}, year = 2023, editor = {Ivaldi, Gilles and Zankina, Emilia}, pages = {156-167}, address = {Brussels}, abstract = {Russia's fresh attack on Ukraine and its many international and national repercussions have helped to revive the fortunes of Germany's main radical right-wing populist party 'Alternative for Germany' (AfD). Worries about traditional industries, energy prices, Germany's involvement in the war and hundreds of thousands of refugees arriving in Germany seem to have contributed to a modest rise in the polls after a long period of stagnation. However, the situation is more complicated for the AfD than it would appear at first glance. While many party leaders and the rank-and-file have long held sympathies for Putin and more generally for Russia, support for Ukraine is still strong amongst the German public, even if there is some disagreement about the right means and the acceptable costs. At least some AfD voters are appalled by the levels of Russian violence against civilians, and the party's electorate is divided as to the right course of action. To complicate matters, like on many other issues, there is a gap in opinion between Germany's formerly communist federal states in the East and the western half of the country. As a result, the AfD leadership needs to tread carefully or risk alienating party members and voters in the more populous western states. Beyond the AfD, the current and future consequences of the war have galvanised the larger far-right movement, particularly in the East. Moreover, they have led to further tensions in the left-wing populist "Linke" (left) party, which is traditionally pacifist and highly sceptical of NATO. The majority of the party tries to square commitment to these principles with solidarity with the victims of Russian aggression. A small but very visible faction, however, shows at least a degree of support for Russia and blames NATO and the US for the war.}, doi = {10.55271/rp0020} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “Regionalvertretungswechsel von links nach rechts? Die Wahl von Alternative für Deutschland und Linkspartei in Ost-West-Perspektive.” Wahlen und Wähler – Analysen aus Anlass der Bundestagwahl 2017. Eds. Schoen, Harald and Bernhard Wessels. Wiesbaden: Springer, 2021. 61-80. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-33582-3_4

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [Download PDF] [HTML] [DATA]Bei der Bundestagswahl 2017 zeigten sich wiedereinmal dramatische Ost-West-Unterschiede. Diese gingen vor allem auf den überdurchschnittlichen Erfolg von AfD und LINKE in den neuen Ländenr zurück. Die AfD ist vor allem in Thüringen und Sachsen besonders stark , die LINKE in Berlin, aber auch in den Stadtstaaten Bremen und Hamburg sowie in einigen westdeutschen Großstädten. Die Wahlentscheidung zugunsten beider Parteien wird sehr stark von Einstellungen zum Sozialstaat (im Falle der Linkspartei) sowie zur Zuwanderung (im Falle der AfD) bestimmt. Beide Parteien profitieren überdies von einem Gefühl der Unzufriedenheit mit dem Funktionieren der Demokratie. Sobald für diese Faktoren kontrolliert wird, zeigt sich, dass die AfD keinen davon unabhängigen “Ost-Bonus” genießt. Zugleich deuten die Modellschätzungen auf substantielle Einflüsse auf der Wahlkreisebene hin. Im Falle der Linkspartei bleibt dagegen ein substantieller Effekt des Befragungsgebietes erhalten, selbst wenn für die Einstellungen kontrolliert wird. Signifikante Differenzen zwischen den Wahlkreisen gibt es hier nicht.

@InCollection{arzheimer-2019, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {Regionalvertretungswechsel von links nach rechts? Die Wahl von Alternative für Deutschland und Linkspartei in Ost-West-Perspektive}, booktitle = {Wahlen und Wähler - Analysen aus Anlass der Bundestagwahl 2017}, publisher = {Springer}, year = 2021, data = {https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/Q2M1AS}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/afd-linkspartei-ostdeutschland/}, url = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/afd-linkspartei-ostdeutschland.pdf}, doi = {10.1007/978-3-658-33582-3_4}, editor = {Schoen, Harald and Wessels, Bernhard}, pages = {61-80}, abstract = {Bei der Bundestagswahl 2017 zeigten sich wiedereinmal dramatische Ost-West-Unterschiede. Diese gingen vor allem auf den überdurchschnittlichen Erfolg von AfD und LINKE in den neuen Ländenr zurück. Die AfD ist vor allem in Thüringen und Sachsen besonders stark , die LINKE in Berlin, aber auch in den Stadtstaaten Bremen und Hamburg sowie in einigen westdeutschen Großstädten. Die Wahlentscheidung zugunsten beider Parteien wird sehr stark von Einstellungen zum Sozialstaat (im Falle der Linkspartei) sowie zur Zuwanderung (im Falle der AfD) bestimmt. Beide Parteien profitieren überdies von einem Gefühl der Unzufriedenheit mit dem Funktionieren der Demokratie. Sobald für diese Faktoren kontrolliert wird, zeigt sich, dass die AfD keinen davon unabhängigen "Ost-Bonus" genießt. Zugleich deuten die Modellschätzungen auf substantielle Einflüsse auf der Wahlkreisebene hin. Im Falle der Linkspartei bleibt dagegen ein substantieller Effekt des Befragungsgebietes erhalten, selbst wenn für die Einstellungen kontrolliert wird. Signifikante Differenzen zwischen den Wahlkreisen gibt es hier nicht.}, address = {Wiesbaden}, dateadded = {01-04-2019} } - Arzheimer, Kai and Carl Berning. “How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and Their Voters Veered to the Radical Right, 2013-2017.” Electoral Studies 60 (2019): online first. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [Download PDF] [HTML]Until 2017, Germany was an exception to the success of radical right parties in postwar Europe. We provide new evidence for the transformation of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) to a radical right party drawing upon social media data. Further, we demonstrate that the AfD’s electorate now matches the radical right template of other countries and that its trajectory mirrors the ideological shift of the party. Using data from the 2013 to 2017 series of German Longitudinal Elections Study (GLES) tracking polls, we employ multilevel modeling to test our argument on support for the AfD. We find the AfD’s support now resembles the image of European radical right voters. Specifically, general right-wing views and negative attitudes towards immigration have become the main motivation to vote for the AfD. This, together with the increased salience of immigration and the AfD’s new ideological profile, explains the party’s rise.

@Article{arzheimer-berning-2019, author = {Arzheimer, Kai and Berning, Carl}, title = {How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and Their Voters Veered to the Radical Right, 2013-2017}, journal = {Electoral Studies}, year = 2019, doi = {10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004}, volume = {60}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/alternative-for-germany-voters}, url = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/alternative-for-germany-party-voters-transformation.pdf}, pages = {online first}, abstract = {Until 2017, Germany was an exception to the success of radical right parties in postwar Europe. We provide new evidence for the transformation of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) to a radical right party drawing upon social media data. Further, we demonstrate that the AfD's electorate now matches the radical right template of other countries and that its trajectory mirrors the ideological shift of the party. Using data from the 2013 to 2017 series of German Longitudinal Elections Study (GLES) tracking polls, we employ multilevel modeling to test our argument on support for the AfD. We find the AfD's support now resembles the image of European radical right voters. Specifically, general right-wing views and negative attitudes towards immigration have become the main motivation to vote for the AfD. This, together with the increased salience of immigration and the AfD's new ideological profile, explains the party's rise.}, dateadded = {01-04-2019} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “‘Don’t mention the war!’ How populist right-wing radicalism became (almost) normal in Germany.” Journal of Common Market Studies 57.S1 (2019): 90-102. doi:10.1111/jcms.12920

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [Download PDF] [HTML]After decades of false dawns, the “Alternative for Germany” (AfD) is the first radical right-wing populist party to establish a national presence in Germany. Their rise was possible because they started out as soft-eurosceptic and radicalised only gradually. The presence of the AfD had relatively little impact on public discourses but has thoroughly affected the way German parliaments operate: so far, the cordon sanitaire around the party holds. However, the AfD has considerable blackmailing potential, especially in the eastern states. In the medium run, this will make German politics even more inflexible and inward looking than it already is.

@Article{arzheimer-2019c, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {'Don't mention the war!' How populist right-wing radicalism became (almost) normal in Germany}, journal = {Journal of Common Market Studies}, year = 2019, abstract = {After decades of false dawns, the "Alternative for Germany" (AfD) is the first radical right-wing populist party to establish a national presence in Germany. Their rise was possible because they started out as soft-eurosceptic and radicalised only gradually. The presence of the AfD had relatively little impact on public discourses but has thoroughly affected the way German parliaments operate: so far, the cordon sanitaire around the party holds. However, the AfD has considerable blackmailing potential, especially in the eastern states. In the medium run, this will make German politics even more inflexible and inward looking than it already is.}, volume = {57}, pages = {90-102}, number = {S1}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/right-wing-populism-germany-normalisation}, dateadded = {27-05-2019}, url = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/afd-normalisation-right-wing-populism-germany.pdf}, doi = {10.1111/jcms.12920}, keywords = {EuroReX, AfD} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “The AfD: Finally a Successful Right-Wing Populist Eurosceptic Party for Germany?.” West European Politics 38 (2015): 535–556. doi:10.1080/01402382.2015.1004230

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [Download PDF] [HTML] [DATA]Within less than two years of being founded by disgruntled members of the governing CDU, the newly-formed Alternative for Germany (AfD) party has already performed extraordinary well in the 2013 General election, the 2014 EP election, and a string of state elections. Highly unusually by German standards, it campaigned for an end to all efforts to save the Euro and argued for a re-configuration of Germany’s foreign policy. This seems to chime with the recent surge in far right voting in Western Europe, and the AfD was subsequently described as right-wing populist and europhobe. On the basis of the party’s manifesto and of hundreds of statements the party has posted on the internet, this article demonstrates that the AfD does indeed occupy a position at the far-right of the German party system, but it is currently neither populist nor does it belong to the family of Radical Right parties. Moreover, its stance on European Integration is more nuanced than expected and should best be classified as soft eurosceptic.

@Article{arzheimer-2015, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {The AfD: Finally a Successful Right-Wing Populist Eurosceptic Party for Germany?}, journal = {West European Politics}, year = 2015, volume = 38, pages = {535--556}, doi = {10.1080/01402382.2015.1004230}, keywords = {gp-e, cp, eurorex}, abstract = {Within less than two years of being founded by disgruntled members of the governing CDU, the newly-formed Alternative for Germany (AfD) party has already performed extraordinary well in the 2013 General election, the 2014 EP election, and a string of state elections. Highly unusually by German standards, it campaigned for an end to all efforts to save the Euro and argued for a re-configuration of Germany's foreign policy. This seems to chime with the recent surge in far right voting in Western Europe, and the AfD was subsequently described as right-wing populist and europhobe. On the basis of the party's manifesto and of hundreds of statements the party has posted on the internet, this article demonstrates that the AfD does indeed occupy a position at the far-right of the German party system, but it is currently neither populist nor does it belong to the family of Radical Right parties. Moreover, its stance on European Integration is more nuanced than expected and should best be classified as soft eurosceptic. }, data = {https://hdl.handle.net/10.7910/DVN/28755}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/afd-right-wing-populist-eurosceptic-germany}, url = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/afd-right-wing-populist-eurosceptic-germany.pdf} }

Discover more from kai arzheimer

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Literature review: declining system support as a consequence of identification with an anti-system party

Söderlund and Kestilä-Kekkonen (2009) were among the first authors to point out that the traditional view of a beneficial link between partisanship and system support may be too simplistic in the presence of electorally relevant radical right parties. They argue that party identification may have a “dark side” akin to the dark side of (bonding) social capital (Söderlund and Kestilä-Kekkonen 2009, 159–60). While Söderlund and Kestilä-Kekkonen (2009) do not fully develop the argument, this notion closely resembles the idea of an echo chamber, where partisans chiefly communicate amongst each other.

Using data from the 2002/2003 wave of the European Social Survey, they focus on three countries with strong radical right parties: Austria, Denmark, and Sweden. Their main finding is that respondents who voted for a radical right party in Denmark and Sweden and also felt close to this party reported lower trust in parliament. They found no such effect in Austria, where the radical right FPÖ was part of the governing coalition at the time. Söderlund and Kestilä-Kekkonen (2009) conclude that a cordon sanitaire strategy may undermine trust in the political system amongst supporters of the radical right.

Anderson and Just (2013) make a similar but somewhat more elaborate argument. They posit that “not all parties are equally fond of the political status quo, and their supporters’ views reflect this variation as a result” (Anderson and Just 2013, 340). This is because different parties have “different positions about the desirability of existing political institutions” (Anderson and Just 2013, 338), which they communicate to their partisans.

According to this “party persuasion” perspective (Anderson and Just 2013, 340), partisans are receptive to in-party messages about the constitutional order, broadly defined. Using expert data on each party’s office-vs-policy orientation and seat-vote disproportionality as instruments, Anderson and Just (2013) find that the in-party’s position towards the constitutional status quo has a strong effect on both satisfaction with the way democracy works and on external efficacy in 15 democracies covered by the 1996-2000 module of the CSES (Anderson and Just 2013, 353).

Theory and measurement: A fresh look at party identification and system support

The contributions by Söderlund and Kestilä-Kekkonen (2009) and by Anderson and Just (2013) represent important steps towards a better understanding of the link between party identification and system support, but they also raise a number of follow-up questions. In this section, I will discuss three of them.

Conceptualisation and mechanisms

Söderlund and Kestilä-Kekkonen (2009) do not really discuss the question of how identifying with the radical right can reduce political trust. Presumably, the fundamental nature of the radical right’s opposition to the liberal elements of democracy appeared obvious to them. Similarly, Anderson and Just do not discuss why some parties prefer principled opposition to government participation, and their notion of a lacking “fondness” for the “political” or “constitutional status quo” (that is then transmitted to the respective party’s identifiers) remains vague. Moreover, it is not entirely clear if policy orientation and underrepresentation are just indicators for or also (partial) causes of this scepticism.

The concept of anti-system parties, that was first proposed by Sartori (1966, 1976), provides a much clearer label for the phenomenon that these authors describe. Although the notion of what it means to be “anti-system” has been repeatedly re-assessed in the intervening decades (Capoccia (2002; Zulianello 2018), see also Zulianello (2019) for a review of related concepts), the literature agrees that in the most general sense, anti-system parties are parties that would, if given the opportunity, change not just government policy but also the “metapolicies” (Zulianello 2018) including “the very system of government” (Sartori 1976, 133). Their opposition to the status quo is stable, ideological, and fundamental. The newer literature agrees that this opposition need not be confined to positions that are formally enshrined in the constitution but may also “encompass other crucial dimensions of political conflict, such as major economic and social issues” (Zulianello 2018, 659) and hence correspond to what Anderson and Just (2013) call the “status quo”.

Besides this ideological dimension, there is also a “relational” (Capoccia 2002, 13) or “systemic integration” (Zulianello 2018, 662) aspect to a party’s anti-systemness, which refers to its interactions with other parties. This throws an interesting light on Söderlund and Kestilä-Kekkonen (2009)’s Austrian findings: the FPÖ of the early 2000s is a textbook case of a “halfway” party that enters coalitions but rejects “one or more of the crucial factors of the status quo ideologically” (Zulianello 2018, 668).

More generally, far right parties are currently the most important anti-system parties in democratic societies, because they are proponents of an identity based on ethnicity and reject many of the liberal elements of democracy (Mudde 2007, 26). They vocally communicate these positions to their supporters, which should lead to the party persuasion effect posited by Anderson and Just (2013). Of course, this does not rule out that there are also effects of the partisan bonding to which Söderlund and Kestilä-Kekkonen (2009) allude. Conversely, the literature suggests that both mechanisms are equally plausible and may complement each other.

The first mechanism is based on an idea that can be traced back to at least the 1980s: Partisans are more likely to be persuaded by messages from in-party elites while they tend to discount messages from out-parties. This insight has spawned a (now very large) literature on party cues (see Harteveld, Kokkonen, and Dahlberg 2017, 1180–81), which demonstrates that party identification can have a powerful causal effect on other political attitudes.

At the same time, there is strong evidence that many citizens prefer to associate with co-partisans, leading to contact networks where political attitudes are relatively homogeneous and hence may reinforce each other. While such homophily is most often discussed in the context of digitally mediated social networks such as Facebook or Twitter, political and partisan echo chambers exist in the offline world, too, even in relatively new, fragmented, and volatile party systems (see e.g. Hrbková, Voda, and Havlík 2023).

While partisan cues and chambers are frequently discussed in the context of the rise of the radical right, they apply to other types of (anti-system) parties as well. The concept of anti-system parties is a general and abstract one. Everything in the next sections should apply, mutatis mutandis, to members of other party families that strive for a fundamental change of the political system.

System support and its operationalisation

According to Easton’s classic perspective, diffuse support — “a reservoir of favorable attitudes or good will” (Easton 1965, 273) — is essential for the long-term survival of any political system. Without such generalised and durable support from the citizenry, regimes need to invest in specific incentives, i.e. benefits and sanctions, to safeguard their rule, which can be both costly and risky. For democracies in particular, a lack of diffuse support is also a major normative problem.

Although the importance of the systems approach as a grand theory of the social sciences has faded, the notion that diffuse support is essential for the stability of any political system has remained central to the study of democratic consolidation, backsliding, and survival. However, there is an ongoing debate about its exact conceptualisation and operationalisation.

An important landmark is Easton’s (1975) own “reassessment” of his original ideas. Against the backdrop of the survey-based research of his time that seemed to show a “crisis of governability”, he developed a complex conceptualisation based on (1) a hierarchy of possible objects of support, (2) a distinction between two major modes of support (diffuse and specific), and (3) a further differentiation of the latter into legitimacy and trust.

Reflecting on an additional quarter century of empirical comparative research into the structure and distribution of political support, Norris (1999) deftly streamlined this conceptualisation. She merged Easton’s distinctions between specific and diffuse support on the one hand and his hierarchy of more or less durable objects of support (political community, system values, processes and structures, and incumbents) on the other into a single dimension. Her stated aim in this was not just to make the concept more tractable, but also to closely align it with the mostly standardised indicators available in countless national and comparative surveys.

Norris’s idea of a continuum of support that runs from the diffuse and fundamental to the specific and ephemeral has widely been adopted, because it provides a useful frame of reference. Its logic undergirds most studies that treat levels of durable support for system values and core institutions as important markers of democratic health. Moreover, measures of diffuse support such as trust or perceived legitimacy also gauge the relative and absolute power of specific institutions within a given political system: an actor that can rely on a “reservoir of good will” has much better chances to prevail in a political struggle than one who is seen as untrustworthy and illegitimate. This latter idea applies to all institutions (and authorities) but is particularly well developed in the literature on high courts (see Sternberg, Brouard, and Hönnige 2022, for a review of this debate).

Against this backdrop, the operationalisations chosen by Anderson and Just (2013) and by Söderlund and Kestilä-Kekkonen (2009), respectively, are less than ideal. Both use measures of support for the political system that are prone to short-term effects and more generally to winner/loser status. Put differently, they are closer to the ’specific’ than to the ’diffuse’ pole of the continuum.

Conceptually, satisfaction with the way democracy works may be a measure of perceived regime performance (Norris 1999; Linde and Ekman 2003). In practice, Anderson himself has demonstrated in his earlier work that citizens who voted for a winning party are more satisfied with democracy than the supporters of losing parties (see also Singh and Mayne 2023, 8). This even holds in contexts where support for democratic principles is generally high (Linde and Ekman 2003, 405). By the same token, it is not surprising that supporters of parties that are marginal and/or disadvantaged by the electoral system perceive themselves as less than efficacious.

Trust in institutions as used by Söderlund and Kestilä-Kekkonen (2009) is therefore a better indicator for gauging the effect of anti-system party identification on diffuse, long-term political support.3 However, trust in party political institutions such as parliament and politicians (Söderlund and Kestilä-Kekkonen 2009, 161) is also prone to suffer from bias due to losers’ discontent.

Trust in a high-profile, but not party political institution such as a constitutional court, is therefore an attractive alternative. Writing about the US Supreme Court, Citrin and Stoker (2018, 54) note that although public support responds to major decisions and appointments, “party identification is not central to the scholarship on trust in the Supreme Court”, because trust has remained high over the 1976-2016 period (Citrin and Stoker 2018, 53) and is hardly affected by partisan polarisation (Citrin and Stoker 2018, 56).

Although the Supreme Court is in some ways a unique institution and may enjoy particularly high levels of support because of its age (see Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird 1998), most European countries have adopted a process of constitutional review, initially proposed by Austrian legal theorist Hans Kelsen, that shares similarities with but also exhibits subtle differences from the American model (Stone Sweet 2002, 79–80). In the Kelsenian system, constitutional courts are distinct from the ordinary judiciary as they exclusively engage in the process of constitutional review, holding a monopoly in this regard. Within this remit, they can declare any action of other state authorities, including decisions by ordinary courts and acts of parliament, null and void.

Constitutional courts thus exist in a “space” of their own (Stone Sweet 2002, 80) adjacent to but separate from the political and the judicial spheres. While their decisions have political consequences, constitutional courts are therefore not ostensibly party political institutions. Moreover, as they embody the political system’s normative core, they represent the deliberative and counter-majoritarian principles that have become the target of populist mobilisation against liberal democracy.

Finally, even if this is not the focus of this article, the aforementioned rich literature on diffuse support for high courts provides additional context for the findings presented here. This makes trust in constitutional courts a particularly interesting indicator for investigating the link between anti-system party identification and political support.

Data and design

Both Söderlund and Kestilä-Kekkonen (2009) and Anderson and Just (2013) argue that party identification is responsible for lower levels of system support, but their analyses rely on cross-sectional survey data. This raises questions about the authors’ causal interpretation of their findings.

On the surface, Anderson and Just’s instrumental variables design is somewhat stronger than that of Söderlund and Kestilä-Kekkonen (2009), because it appears very unlikely that the respondents’ answers could somehow cause the experts’ assessment of a party’s primary goal or the mechanical disproportionality the party faces in elections. Using instruments for outsider status instead of raw expert ratings does, however, not guard against a different type of reverse causality: it is quite possible (and even plausible) that respondents who are particularly unhappy with the state of democracy and perceive their external efficacy as low become supporters of an anti-system party. In that case, the link between partisanship and low system support would not, or not exclusively, result from party persuasion or an echo chamber effect, but from self-selection by the respondents. Confounder bias would lead one to overestimate the negative effect of party identification on system support.

With observational data, one can of course never rule out such bias and hence never fully identify causal effects. Having said that, open, population-representative panel studies4 may provide valuable additional insights into the link between party identification and system support, especially when they are conducted in an environment where a new anti-system party emerges. More specifically, the fixed effects panel estimator, discussed in the section after the next, can eliminate a whole host of person-specific confounders. It is, however, important to note that using panel data usually requires abandoning the comparative perspective.

Case selection: identification with “Alternative for Germany” and trust in the Federal Constitutional Court

Germany, an established liberal democracy, is singularly well suited to examine the link between identification with an anti-system party and declining diffuse support for the political system for a number of reasons.

First, Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court (FCC) closely resembles the Kelsenian ideal. Set up after the Second World War as the guardian of the new democratic constitution, it quickly became a powerful veto player (Brouard and Hönnige 2017) and one of the country’s most respected institutions. Unlike some other European high courts (see Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird 1998), it enjoys very high level of public support. This near-universal approval continues to the present day. In the 2018 German General Social Survey (ALLBUS), the court emerged as the most trusted of eleven institutions (tied with the higher education system), achieving an average score of 4.2 on a scale ranging from 0 to 6. For comparison, trust in the federal parliament was considerably lower at 3.2. These high levels of trust may even give the FCC the ability to legitimise or de-legitimise specific policies (Sternberg, Brouard, and Hönnige 2022).

Second, Germany also features a relatively new anti-system party. “Alternative for Germany” (AfD) was only founded in 2013.5 They won their first seats in the 2014 European parliamentary election and a string of state elections later that year. The AfD initially campaigned on a soft-eurosceptic centre-right platform (Arzheimer 2015). In 2015, they began to turn into a prototypical populist radical right party focused on the issues of immigration, asylum, and multi-culturalism, while the relative importance of soft euroscepticism declined for both the AfD and their voters (Arzheimer and Berning 2019). This transformation was complete by 2016.

In 2017, when they became the first far right party since the 1950s to enter the federal parliament (Bundestag), the most radically nativist faction within the party had clearly won out (Pytlas and Biehler 2023). As a result, the transformed AfD maintains links with openly right-wing extremist actors and tolerates extremist tendencies within. This makes it easier for other German parties to establish, maintain and justify a cordon sanitaire around the AfD. From 2016 on, the AfD therefore fulfils both criteria for anti-system status: it is radically opposed to the constitutional and political status quo and excluded from interactions with other parties.

At the same time, the AfD has been electorally relevant since 2014. Their relatively high level of support makes it comparatively easy to study the small fraction of their supporters who claim to be party identifiers with random population samples.

Unlike previous anti-system parties such as the NPD, the AfD is also able to effectively communicate their positions to not just their members but also to (potential) supporters and the wider electorate. They employ a strategy of deliberate and calculated provocations to secure extensive coverage by legacy media (Maurer et al. 2023). At the same time, they have cultivated an audience on social media which dwarves that of all other parties (Serrano et al. 2019). Moreover, in some of their local and regional strongholds, the AfD is numerically the strongest party and closely embedded in networks that link members, partisans, and other far right actors (Deodhar 2020). All this suggests that there is ample potential for both partisan cues and echo chamber effects.

Third, by a lucky coincidence, GESIS Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences institute, a large public research infrastructure, launched a new panel study in 2013 just before the AfD ran its first ever election campaign, thus providing a clean baseline. This unique constellation makes Germany and the AfD a particularly attractive case for the present analysis. While electorally relevant anti-system parties have been part of the socio-political fabric for years and even decades in many countries, the AfD (and partisan attachment to it) could not possibly exert an influence on respondents before 2014. With the GESIS panel, which is freely accessible for outside researchers, it is possible to monitor the emergence of AfD identifications and track their consequences during the party’s first parliamentary cycle, from their failed bid to enter the Bundestag in 2013 to their breakthrough election in 2017.

Data and methods

Data: the GESIS panel

The GESIS panel started in 2013 with a large (N=4938) probability sample from the general (German-speaking) population (Bosnjak et al. 2018).6 Since then, respondents have been interviewed up to four times per year, either web-based or by mail.

While not all items are included in each wave, information on trust in the FCC was collected first in June/July 2013 and then every year in April/May. Values for trust range from 1 (no trust at all) to 7 (trust fully).

The German standard item on party identification7 was also included once per year from 2014. For the purpose of the analysis, responses were recoded to a value of 1 for AfD identifiers and 0 for all other respondents.

In 2013, everyone was assigned a value of 0, because the AfD had only existed for a couple of months when information on trust in the FCC was collected, whereas party identification takes time and familiarity to develop. Information on party identification was collected in April 2014, 2015 (before the de-facto split), and 2016. In 2017, trust was measured in April as usual, but information on party identification was only collected in a separate wave in December 2017.8 However, excluding the observations from 2017 does not substantively alter the empirical findings (see Tables [table-2] and 3 in the appendix).9

A further complication arises from changes in the format of the party identification question. In 2014 and 2017, respondents were presented with a list of options that included the AfD and could also choose “no party” or “another party”. In 2015 and 2016, the list did not include an explicit AfD option so that AfD identifiers were lumped together with supporters of smaller parties in the “other” category. While this is obviously unfortunate, the AfD had at this time already begun to absorb the electorate of other right-wing parties such as the NPD, so it seems safe to assume that most of these “other” partisans were in fact AfD supporters. Moreover, most of the “other” parties could be classified as anti-system, too. Following this logic, respondents who chose the “other” option in 2015 and 2016 were coded as having an AfD identification while everyone else was coded as 0. For a robustness check, the (few) respondents who chose “other” in 2014 and 2017 were recoded as AfD partisans. Again, this does not alter the conclusions from the analysis (see Table [table-3] and Figure 4 in the appendix).

Methods: fixed effects panel regression

The main hypothesis developed in the previous sections is this: Identification with an anti-system party (here: Alternative for Germany) causes a reduction of diffuse support for the political system, measured by trust in the FCC (H1a).

Having repeated observations of the same respondents is advantageous for attempting to isolate this causal effect of party identification on trust, compared to a single cross-sectional study. This is because any analysis of the link between party identification and political support is faced with a fundamental challenge: respondents cannot be randomly assigned to party identification groups but rather self-select to identify with an anti-system party (or not), based on their predispositions. As a consequence of that, two potential problems arise. First, it is possible that respondents with lower levels of support are more likely to take up an identification with an anti-system party (reverse or reciprocal causality). Second, unobserved background variables (e.g. ideology or personality) may cause low levels of system support and a higher likelihood to identify with an anti-system party. Both mechanisms would lead to bias that overstates the effect of party identification on system support.

Not much can be done about the first problem,10 although it seems not very likely that a negative orientation towards a specific institution would in itself strongly increase the likelihood of identification with a specific party.11 Panel data do, however, provide some leverage for addressing the second problem: respondents who change their party identification over time may act as their own control (Allison 2009), as they are observed with and without the “treatment”.

More specifically, fixed effects (FE) panel regression models (Brüderl and Ludwig 2015) include a respondent-specific error term that is not required to be independent from the time-variant regressors. This term absorbs any individual time-invariant background variables that could potentially affect both party identification and trust in the FCC. Fixed effects estimates of AfD identification’s effect on trust are therefore not biased by stable unobserved background variables.

There may also be time-variant background variables that are not respondent-specific, i.e. period effects. Political events such as the so-called refugee crisis could simultaneously reduce system support and increase the number of AfD identifiers, thereby creating a spurious correlation between the variables. Such global shifts in public opinion can be accommodated by including a vector of fixed effects for the survey year.

Finally, the effect of AfD party identification on trust need not be stable over time. As mentioned above, the AfD’s ideology and communication have become increasingly radical over time, raising the party’s anti-system profile. Therefore, the effect of identification with the AfD should be more pronounced towards the end of the observation period (H1b).

Additionally, it is also possible that AfD identifiers react differently to political events captured by the period effects, because they respond to partisan framing cues (possibly as a consequence of party persuasion effects). To account for both types of heterogeneity in the effect of AfD identification, the model includes a vector of interaction effects:

It is, however, important to note that even a panel design cannot safeguard against a final potential source of bias: unobserved person-specific time-variant background variables. It is at least conceivable that intra-individual changes (i.e. an independent and individual radicalisation over time) could affect both trust and identification, which would in turn bias estimates of the causal effect of party identification on trust.

This leaves one final issue: the disturbances () are unlikely to meet the standard assumptions of identical and independent distribution (i.i.d.): presumably, they will be heteroscedastic and autocorrelated within respondents, which may produce overly optimistic standard errors. Therefore, cluster-robust standard errors are reported in the next section.

Results

Descriptive findings

Using the coding scheme outlined above, there are 4373 respondents for whom information on both trust and AfD identification is available for the same year at least once. For 85.2 per cent of these respondents, there is complete information from at least two years. The average number of complete observations per respondent is 3.5. While panel attrition is always a concern, its extent is not excessive. Just seven per cent of the respondents dropped out after the first year, and a further 9 per cent after the second year. Moreover, some respondents have missing values for one year, but return to the panel during the next. Data for the last year under study (which were collected in two separate waves) are available for 2498 respondents (57 per cent of the original sample).

The number of AfD identifiers is low and varies between 107 (in 2015) and 160 (in 2017). Based on 11415 observed transitions, the probability of acquiring an AfD identification is very low (3 per cent), whereas the probability of retaining such an identification from one year to the next is 51 per cent. Figure 2 in the appendix shows all transitions across the 2013-2017 period.

Overall, trust in the FCC is high with a mean of 4.8 and a standard deviation of 1.6 across all observations, but was markedly lower (by 0.1 points) in 2015 and 2016. Intra-individual variation is substantially smaller than variation between respondents (=0.85 vs =1.37). Finally, across all observations trust is a whole scale point lower for AfD identifiers than for respondents who do not identify with the AfD.

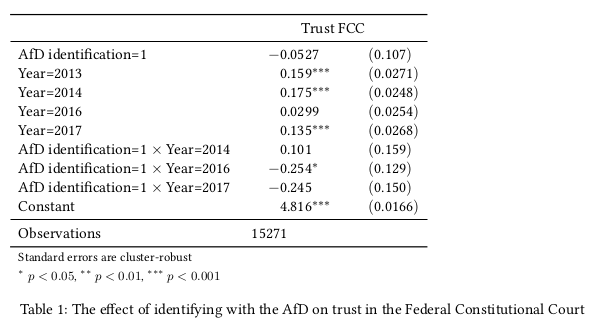

Panel regression

Table [table-1] shows the estimates for the fixed effects panel regression. For the reference year of 2015 (the midpoint of the period under study), the effect of identifying with the AfD is negative but not significantly so. The period effects for all years but 2016 are positive and substantial, confirming that 2015-2016 was indeed a phase of political crisis in Germany. Moreover, the interaction effects for 2016 and 201712 are negative and rather large, pointing to a significant gap between AfD supporters and the other respondents.

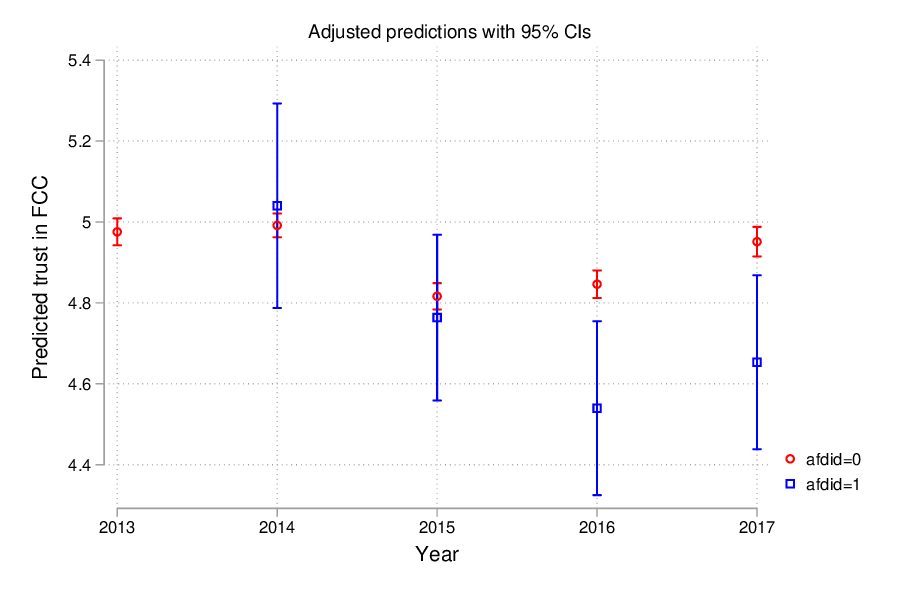

However, the significance and impact of interactions is best assessed graphically (Brambor, Clark, and Golder 2006). Figure 1 shows the expected levels of trust over time for both AfD identifiers and other respondents. Confidence intervals for the former are very wide, because this group is so small. Nonetheless, the picture that emerges is remarkably clear.

For the non-identifiers, trust in the FCC declined by almost 0.2 scale points in 2015 and 2016, but bounced back in 2017. For the AfD identifiers, model-based estimates of trust in the court were indistinguishable from those of all other respondents in 2014 and 2015. Put differently, their trust levels dropped in 2015, but not more than those of the other respondents.

Yet in 2016, when the AfD’s transformation into a radical right party was complete, a large and statistically significant gap opened up between both groups. Trust levels amongst AfD identifiers were now 0.3 scale points lower than amongst other respondents, and almost 0.5 points lower than they had been in 2014. Importantly, the gap between AfD identifiers and all other respondents did not close in 2017. While trust increased somewhat amongst AfD supporters as well, the difference of 0.3 points between both groups remained essentially unchanged even after trust returned to its initial levels for the non-identifiers.

These findings suggest that identification with the AfD exerts a politically relevant negative effect on diffuse system support once the AfD has completed its transformation into a fully-fledged anti-system party. This is in line with hypotheses H1a and H1b.

Crucially, the AfD has not in any way attacked the FCC during this period, and the court has done nothing to attract the wrath of AfD partisans. This further strengthens the notion that trust in the FCC is a good indicator of diffuse system support.

Moreover, the conclusions do not depend on using trust in the FCC as an operationalisation of system support. The same pattern holds for a range of alternative indicators: trust in the ordinary courts, trust in then national parliament, or satisfaction with the way democracy works in Germany. As additional analyses (documented in the appendix) show, re-estimating the model with these indicators as the dependent variables yields essentially identical results.

Limitations

Could alternative mechanisms be responsible for the link between AfD identification and lowered system support? FE estimates are unaffected by omitted variable bias resulting from stable person-specific confounders such as personality or effects of socialisation. The model also controls for period effects that could affect both party identification and trust, and for period-specific heterogeneity in the effect of AfD identification.

Feedback effects and/or reverse causality cannot be ruled out completely, yet appear unlikely, especially as swapping trust in the FCC for trust in the ordinary courts yields very similar findings. However, one cannot rule out that in some respondents, independent and individual radicalisation journeys could cause both a decline in trust and an increased likelihood of identifying with the AfD.

Even so, the estimates are more conservative than the previous ones based on cross-sectional data, and yet, their magnitude is substantial. This strongly suggests that identification with an anti-system party does reduce system support. Whether this happens primarily through party persuasion, through communication with co-partisans, or through a mixture of both remains an open question for future research.

Conclusion

Surprisingly little is known about the impact of identification with an anti-system party on system support. The few existing studies suggest that such identifications undermine diffuse support for the political system. But these analyses are based on data that are more than two decades old and possibly overestimate the size of the effects.

Using the unique setting of a panel survey that tracks the rise of a new party, the analysis presented here shows that identification with a radical right anti-system party, Alternative for Germany, does indeed reduce trust in the FCC by a considerable margin. This is of scientific as well as of practical importance, because the FCC is a generally popular institution that embodies and protects the liberal and anti-majoritarian principles of Germany’s constitution. Crucially, this negative effect only appears after the AfD’s transformation into a fully-fledged anti-system party and thus confirms the older results of Söderlund and Kestilä-Kekkonen (2009) and Anderson and Just (2013).

These findings have implications beyond the AfD, Germany, and even the radical right. Anti-system parties, broadly defined (Zulianello 2019), have grown stronger in recent decades whilst becoming more extreme (Wagner and Meyer 2017). Even when they enter government, they show no signs of moderation but remain “halfway actors”, committed to an illiberal agenda (Albertazzi and McDonnell 2015) and even willing to use the apparatus of the state to dismantle democratic principles (Peters and Pierre 2019).

It has long been acknowledged that anti-system parties also undermine the psychological basis of democracy by fostering affective polarisation within the citizenry. However, the causal link between identification with anti-system parties and a decline in trust toward core liberal democratic institutions highlights another, hitherto understudied, way in which these parties contribute to democratic backsliding: through communication with and among their core supporters, they may be able to diminish diffuse support for the political system itself. Future research needs to explore the mechanisms involved as well as the potential strategies to counteract them.

References

Albertazzi, Daniele, and Duncan McDonnell. 2015. Populists in Power. Routledge Studies in Extremism and Democracy 24. London, New York: Routledge. http://scans.hebis.de/HEBCGI/show.pl?35716042_toc.pdf.

Allison, Paul D. 2009. Fixed Effects Regression Models. Sage University Papers. Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences 160. Beverly Hills, London, New Delhi: Sage.

Anderson, Christopher J., and Aida Just. 2013. “Legitimacy from Above: The Partisan Foundations of Support for the Political System in Democracies.” European Political Science Review 5 (3): 335–62. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773912000082.

Arzheimer, Kai. 2015. “The AfD: Finally a Successful Right-Wing Populist Eurosceptic Party for Germany?” West European Politics 38: 535–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2015.1004230.

Arzheimer, Kai, and Carl Berning. 2019. “How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and Their Voters Veered to the Radical Right, 2013-2017.” Electoral Studies 60: online first. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004.

Backer, Susann. 2000. “Right-Wing Extremism in Unified Germany.” In The Politics of the Extreme Right. From the Margins to the Mainstream, edited by Paul Hainsworth, 87–120. London, New York: Pinter.

Bosnjak, Michael, Tanja Dannwolf, Tobias Enderle, Ines Schaurer, Bella Struminskaya, Angela Tanner, and Kai W. Weyandt. 2018. “Establishing an Open Probability-Based Mixed-Mode Panel of the General Population in Germany: The GESIS Panel.” Social Science Computer Review 36 (1): 103–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439317697949.

Brambor, Thomas, William Roberts Clark, and Matt Golder. 2006. “Understanding Interaction Models. Improving Empirical Analyses.” Political Analysis 14 (1): 63–82.

Brouard, Sylvain, and Christoph Hönnige. 2017. “Constitutional Courts as Veto Players: Lessons from the United States, France and Germany.” European Journal of Political Research 56 (3): 529–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12192.

Brüderl, Josef, and Volker Ludwig. 2015. “Fixed-Effects Panel Regression.” In The Sage Handbook of Regression Analysis and Causal Inference, 327–57. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446288146.

Campbell, Ross. 2018. “Persistence and Renewal: The German Left Party’s Journey from Outcast to Opposition.” Contemporary Politics 24 (2): 153–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2017.1392671.

Capoccia, Giovanni. 2002. “Anti-System Parties: A Conceptual Reassessment.” Journal of Theoretical Politics 14: 9–35.

Citrin, Jack, and Laura Stoker. 2018. “Political Trust in a Cynical Age.” Annual Review of Political Science 21 (1): 49–70. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050316-092550.

Dalton, Russell J. 2016. “Party Identification and Its Implications.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.72.

———. 2020. “The Blinders of Partisanship.” In Research Handbook on Political Partisanship, edited by Henrik Oscarsson and Sören Holmberg, 74–88. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788111997.00011.

Dalton, Russell J., and Martin P. Wattenberg, eds. 2000. Parties Without Partisans. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Deodhar, Bhakti. 2020. “Networks of the ‘Repugnant Other’: Understanding Right-Wing Political Mobilization in Germany.” Journal of Advanced Research in Social Sciences 3 (3): 20–32. https://doi.org/10.33422/jarss.v3i3.518.

Diamond, Larry. 2021. “Democratic Regression in Comparative Perspective. Scope, Methods, and Causes.” Democratization 28 (1): 22–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2020.1807517.

Easton, David. 1965. A Systems Analysis of Political Life. New York: Wiley.

———. 1975. “A Re-Assessment of the Concept of Political Support.” British Journal of Political Science 5: 435–57.

Foa, Roberto Stefan, and Yascha Mounk. 2017. “The Signs of Deconsolidation.” Journal of Democracy 28 (1): 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2017.0000.

Gibson, James L., Gregory A. Caldeira, and Vanessa A. Baird. 1998. “On the Legitimacy of National High Courts.” American Political Science Review 92 (2): 343–58. https://doi.org/10.2307/2585668.

Harteveld, Eelco, Andrej Kokkonen, and Stefan Dahlberg. 2017. “Adapting to Party Lines: The Effect of Party Affiliation on Attitudes to Immigration.” West European Politics 40 (6): 1177–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1328889.

Holmberg, Sören. 2003. “Are Political Parties Necessary?” Electoral Studies 22 (2): 287–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-3794(02)00016-1.

Hrbková, Lenka, Petr Voda, and Vlastimil Havlík. 2023. “Politically Motivated Interpersonal Biases: Polarizing Effects of Partisanship and Immigration Attitudes.” Party Politics, online first. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688231156409.

Iyengar, Shanto, Yphtach Lelkes, Matthew Levendusky, Neil Malhotra, and Sean J. Westwood. 2019. “The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States.” Annual Review of Political Science 22 (1): 129–46. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034.

Linde, Jonas, and Joakim Ekman. 2003. “Satisfaction with Democracy: A Note on a Frequently Used Indicator in Comparative Politics.” European Journal of Political Research 42 (3): 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00089.

Maurer, Marcus, Pablo Jost, Marlene Schaaf, Michael Sülflow, and Simon Kruschinski. 2023. “How Right-Wing Populists Instrumentalize News Media: Deliberate Provocations, Scandalizing Media Coverage, and Public Awareness for the Alternative for Germany (Afd).” The International Journal of Press/Politics 28 (4): 747–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612211072692.

McAllister, Ian. 2020. “Partisanship and Political Participation.” In Research Handbook on Political Partisanship, edited by Henrik Oscarsson and Sören Holmberg, 266–80. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788111997.00028.

Mudde, Cas. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 2019. The Far Right Today. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Norris, Pippa. 1999. “Introduction: The Growth of Critical Citizens?” In Critical Citizens. Global Support for Democratic Government, edited by Pippa Norris, 1–27. Oxford u.a.: Oxford University Press.

Peters, B. Guy, and Jon Pierre. 2019. “Populism and Public Administration: Confronting the Administrative State.” Administration & Society 51 (10): 1521–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399719874749.

Pytlas, Bartek, and Jan Biehler. 2023. “The AfD Within the AfD: Radical Right Intra-Party Competition and Ideational Change.” Government and Opposition, online first. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2023.13.

Sartori, Giovanni. 1966. “European Political Parties: The Case of Polarized Pluralism.” In Political Parties and Political Development, edited by Joseph La Palombara and Myron Weinter, 137–76. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

———. 1976. Parties and Party Systems. A Framework for Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Serrano, Juan Carlos Medina, Morteza Shahrezaye, Orestis Papakyriakopoulos, and Simon Hegelich. 2019. “The Rise of Germany’s AfD: A Social Media Analysis.” In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Social Media and Society, 214–23. SMSociety ’19. New York, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.1145/3328529.3328562.

Singh, Shane P, and Quinton Mayne. 2023. “Satisfaction with Democracy: A Review of a Major Public Opinion Indicator.” Public Opinion Quarterly, online first. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfad003.

Söderlund, Peter, and Elina Kestilä-Kekkonen. 2009. “Dark Side of Party Identification? An Empirical Study of Political Trust Among Radical Right-Wing Voters.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 19 (2): 159–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457280902799014.

Sternberg, Sebastian, Sylvain Brouard, and Christoph Hönnige. 2022. “The Legitimacy-Conferring Capacity of Constitutional Courts: Evidence from a Comparative Survey Experiment1.” European Journal of Political Research 61 (4): 973–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12480.

Stone Sweet, Alec. 2002. “Constitutional Courts and Parliamentary Democracy.” West European Politics 25 (1): 77–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/713601586.

Wagner, Markus, and Thomas M. Meyer. 2017. “The Radical Right as Niche Parties? The Ideological Landscape of Party Systems in Western Europe, 1980–2014.” Political Studies 65 (SI): 84–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321716639065.

Waldner, David, and Ellen Lust. 2018. “Unwelcome Change. Coming to Terms with Democratic Backsliding.” Annual Review of Political Science 21 (1): 93–113. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050517-114628.

Zulianello, Mattia. 2018. “Anti-System Parties Revisited: Concept Formation and Guidelines for Empirical Research.” Government and Opposition 53 (4): 653–81. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2017.12.

———. 2019. “Varieties of Populist Parties and Party Systems in Europe: From State-of-the-Art to the Application of a Novel Classification Scheme to 66 Parties in 33 Countries.” Government and Opposition, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2019.21.

1Department of Political Science, University of Mainz, Germany

2Following (Mudde 2019), I use “far right” as a shorthand for both.

3While Norris (1999) puts evaluations of regime institutions somewhat closer to the short-term/specific pole of the support spectrum than assessments of regime performance, Easton (1975, 447) unambiguously defines trust as a durable and diffuse.

4See here: https://openpanelalliance.org/.

5Previous anti-system parties on the far right remained confined to the margins of electoral politics and never gained national representation (Backer 2000). They have become completely irrelevant with the rise of the AfD. On the left, a number of communist splinter parties are clearly anti-system but have virtually no supporters. The larger Left Party is sometimes portrayed as a challenger party and is descended from the post-communist PDS. However, both the contemporary Left Party and their current voters were already well integrated in 2013 (Campbell 2018) and would thus provide no clear-cut case for testing the negative effect of party identification on diffuse system support.

6Because I’m interested in the 2013-2017 period, I use the original cohort. Replacements were recruited in 2016, 2018, and 2021. The German Internet Panel resembles the GESIS panel but only started tracking identifications with the AfD in 2017, when their transformation was already complete, and provides only two additional data points (2020 and 2021).

7“In Germany many people lean towards voting for a certain political party over time, although they tend to vote for another party from time to time. How about you: Do you lean — in general — toward a certain party? And if so, which one?”

8In 2017, party identification was also included in the October wave, but the format of the question was different.

9Replication data and Stata scripts to reproduce the tables and figures are available at REDACTED FOR REVIEW.

10Dynamic panel models that include lagged dependent variables are sometimes touted as a solution for dealing with reciprocal causation, but in practice their estimates are often inconsistent, especially when the number of observations for each respondent is low (Brüderl and Ludwig 2015, 341–42.)

11To the best of my knowledge, the AfD have not made any prominent statements on the court during that period that would have made them particularly attractive for critics of the FCC.

12The model includes no interaction term for the year 2013, because in 2013, all respondents started without an AfD identification.

Discover more from kai arzheimer

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.