Religious prejudice in secular societies?

Islamophobia is everywhere. In the 21st century, Muslims have become the most significant “outgroup” in Western Europe, with the far-right seemingly embracing Christianity. Unlike in the US, however, the majority of far right actors in Western Europe have secular, anti-clerical, or even neo-pagan roots, in one of the most rapidly secularising regions in the world.

Consistent with this, most far right voters have little interest in religion. Therefore, the faith of certain immigrants and their descendants should not be such a big issue.

One prominent explanation for this apparent paradox is that Western European far right actors have developed a rhetorical strategy (“Christianism”) which uses Christianity primarily as a cultural marker that is largely devoid of religiosity but facilitates the “othering” of Muslims. In secular Western Europe, Christianism appears to be an attractive discursive and communication strategy for far right actors.

However, surprisingly little is known about the connection between religiosity, Islamophobia, and populist far-right ideology within Western Europe’s mass belief systems. Existing studies primarily focus on two narrow aspects:

- Religiosity’s impact on far right electoral support

- The link between religion and anti-immigrant/Muslim prejudice, often in isolation from broader far-right attitudes.

New article in Research & Politics

In a new article on Islamophobia and far right attitudes that has just been published in Research & Politics (open access), I analyse survey data from Britain, France, Germany (East & West), and the Netherlands that were collected under the auspices of the SCoRE project to address this gap.

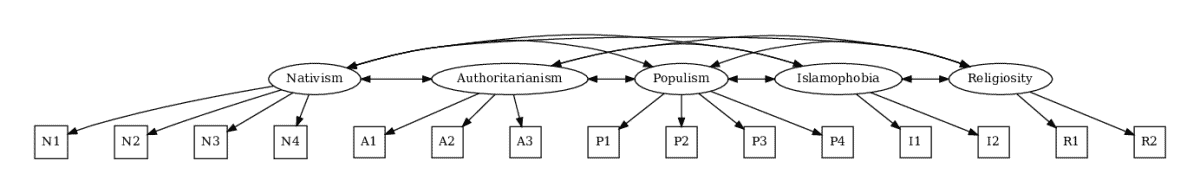

Using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM), I uncover these key findings:

- Religiosity is mostly unrelated to Islamophobia, nativism, right-wing authoritarianism, and populism.

- Islamophobia overlaps with both nativism and authoritarianism and, to a lesser degree, with populism.

- Put differently, individuals who fear immigration/immigrants and advocate for strict laws/harsh enforcement also tend to reject Islam – but not for religious reasons.

Data and replication

The data come from four large online surveys that were carried out in the context of national elections at the tail end of the so-called refugee crisis. Participants were recruited from large access panels. Respondents from Germany’s eastern states were oversampled so that their data can be analysed separately to provide additional contextual variation. Sample sizes vary from 4,031 (Eastern Germany) to 14,399 (Western Germany).

Britain, France, Germany, and the Netherlands were chosen because of their significant Muslim minorities (6-9% of the population) and rapid secularisation, with only 15-22% of the population attending church. All four countries also feature relevant far-right actors.

At the same time, state-church relations and far right traditions vary considerably, yet the results are very similar across contexts. They should therefore generalise well to other West European countries.

Replication data and scripts are available from the journal’s dataverse. Additional graphs and tables can be found in the online appendix.

Implications

The study’s results on mass belief systems in Western Europe are consistent with a “Christianist” strategy employed by radical right parties. Christianism is useful for “othering” Muslims. At the same time, it is devoid of genuine religiosity and any inconvenient appeals to love one’s neighbour.

The absence of a link between religiosity and Islamophobia also helps explain the absence of a genuine, electorally relevant religious far right in Western Europe.

Now read the full, free, short, and sweet article at Research & Politics.

- Arzheimer, Kai. “Islamophobia in Western Europe is unrelated to religiosity but highly correlated with far right attitudes.” Research & Politics 12.3 (2025): online first. doi:10.1177/20531680251351895

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [Download PDF] [HTML]The far right’s relationship with religion has become a major focus of current research. Even in Western Europe, one of the most rapidly secularising areas of the world, far right actors claim to defend Christian values against the alleged threat of Islam and Muslim immigrants, a rhetorical strategy known as ‘Christianism’. Yet, little is known about how religiosity, Islamophobia, and populist far-right ideology are connected at the level of mass belief systems in Western Europe. Most of the literature is focused either on religiosity’s effect on voting or on the connection between religiosity and ethnic prejudice, without considering religiosity’s relationships with the wider spectrum of far-right ideology. The present article fills this gap by analysing survey data from Britain, France, Germany, and the Netherlands. It uses SEM to uncover the relationships between Christian religiosity on the one hand and Islamophobia and far-right attitudes on the other. The results are broadly similar across different contexts: religiosity is mostly unrelated to Islamophobia, nativism, right-wing authoritarianism, and populism. Conversely, Islamophobia overlaps considerably with both nativism and authoritarianism: people who perceive immigration as a threat and favour strict laws and harsh enforcement also tend to reject Islam, but not for religious reasons. This pattern is compatible with the strategy of Christianism, which is largely devoid of religiosity, yet facilitates the “othering” of Muslims as a cultural out-group. It also helps to explain why there is no genuine, electorally relevant religious far right in Western Europe.

@Article{arzheimer-2025b, author = {Kai Arzheimer}, title = {Islamophobia in Western Europe is unrelated to religiosity but highly correlated with far right attitudes}, journal = {Research \& Politics}, year = 2025, volume = 12, number = 3, pages = {online first}, html = {https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/20531680251351895}, abstract = {The far right's relationship with religion has become a major focus of current research. Even in Western Europe, one of the most rapidly secularising areas of the world, far right actors claim to defend Christian values against the alleged threat of Islam and Muslim immigrants, a rhetorical strategy known as 'Christianism'. Yet, little is known about how religiosity, Islamophobia, and populist far-right ideology are connected at the level of mass belief systems in Western Europe. Most of the literature is focused either on religiosity's effect on voting or on the connection between religiosity and ethnic prejudice, without considering religiosity's relationships with the wider spectrum of far-right ideology. The present article fills this gap by analysing survey data from Britain, France, Germany, and the Netherlands. It uses SEM to uncover the relationships between Christian religiosity on the one hand and Islamophobia and far-right attitudes on the other. The results are broadly similar across different contexts: religiosity is mostly unrelated to Islamophobia, nativism, right-wing authoritarianism, and populism. Conversely, Islamophobia overlaps considerably with both nativism and authoritarianism: people who perceive immigration as a threat and favour strict laws and harsh enforcement also tend to reject Islam, but not for religious reasons. This pattern is compatible with the strategy of Christianism, which is largely devoid of religiosity, yet facilitates the "othering" of Muslims as a cultural out-group. It also helps to explain why there is no genuine, electorally relevant religious far right in Western Europe.}, url = {https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/reader/10.1177/20531680251351895}, doi = {10.1177/20531680251351895} }

Discover more from kai arzheimer

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.