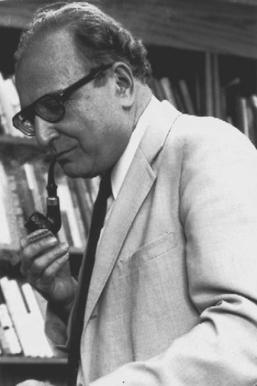

In this house, every day is S.M. Lipset Appreciation Day. Most of what we do and think today is not much more than an elaboration of the old stuff, plus some new data and fancy methods.

And still, I took some sort of mental double take when I stumbled across this article. Somewhat depressingly, he wrote (or at least published) these words almost exactly 70 years ago, in June 1955.

![Seymour Martin Lipset wrote about the Radical Right - in 1955 3 This essay deals with the emergence and activities of an important

| American political phenomenon, the radical right. [I] This group, which

v is characterized as radical because it desires to make far-reaching

changes in American institutions, is basically concerned with eliminating from

American political life those persons and institutions which threaten either

its sense of traditional American values, or economic interests. In general, it

is opposed to the social and economic reforms that have been enacted in the

last twenty years, and to the internationalist pro-British foreign policy pursued

in that period.

The activities of the radical right would be of little interest, except to

students or practitioners of politics, if it sought to achieve its ends through

the traditional democratic procedures of pressure-group tactics, lobbying, and

action at the ballot box. In fact, however, while most individuals and

organizations which should be considered part of the radical right do limit

their activities to these means, some use undemocratic methods as well. It

is a fact that radical right agitation has facilitated the growth of practices

which threaten to undermine the social fabric of democratic politics; this

movement, therefore, must be seriously considered by all those who would

preserve democratic constitutional procedures in this country. The threats

to democratic procedure which are, in part, an outgrowth of radical right

agitation have been documented in great detail by many observers, and it is

not necessary to repeat them here. In brief, they involve attempts to destroy

the right of assembly, the right of petition, the freedom of association, the

freedom to travel, and the freedom to teach or conduct scholarly research

without conforming to political tests.[2]](https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/16022604/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/lipset-radical-right.png)

Discover more from kai arzheimer

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

His 1955 BJS article is so good!